Writers and Hotels, a Love Affair.

Understanding the special relationship between scribes and grand hotels.

There is a particular quality of immutability about a grand hotel. They take up formal residence in a city, adhere to the physical laws of time and space, but remain majestically aloof to the temporal affairs around them. They form relationships with foreign aristocrats, celebrities, and flaneurs, but of revolutions and wars right at home, they care very little.

If you’re lucky to stay at a grand hotel, you’ll find it disrupts your Lonely Planet itinerary, plays for your attention, and always, somehow, calls you back to its secluded corridors or the rooftop bar.

Greatness in a hotel is like style or grace in a person: it comes from the inside-out, more like a soul than a character trait. It’s the “it factor” we’re all attracted to: that precise quality multinational hospitality and management groups want to conjure up with a brand strategy and nouveau riche add-ons.

This ineffable quality is partly due to age, or you might say survivability, but some contemporary hotels can make the grade. These special places have an atmosphere about them—an inscrutable mix of architectural splendor, striking interior design, proximity to landmarks or natural wonders—a truly professional staff (no trivial matter), fascinating historical and present-day guests, the fame of its restaurant or bar, and most importantly, the stories we tell about them.

Decades before the concept of brand, as we know it today, existed, The Oriental Hotel in Bangkok (now Mandarin Oriental, Bangkok) had its own brand cache; a reputation for style, elegance, and a bit of European civilization in equatorial Asia.

Part of this brand, right from the beginning, was literary; not only because writers stayed there, but stories—both by and about writers—began to shape what we thought about the Oriental, as well as those like it.

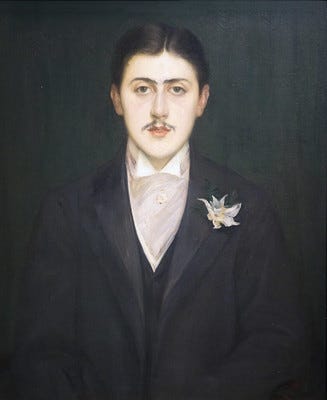

Proust and Le Grand Hôtel.

If your average person has any associations with Marcel Proust (a shaky premise) it will involve madeleine cookies and reclusiveness. As a Proustian, I find the misconception of Proust as a hermit, a puzzling one, because he was relentlessly social throughout his life.

Hotels were a critical part of Proust’s story. Le Grand Hôtel in Cabourg on the Normandy coast (still in operation), was a place of rest, an arena for socializing, and something of a research laboratory for fictional characters. Many of the people he knew from Cabourg, were re-presented in In The Shadow of Young Girls in Flower as guests of the fictional Grand-Hôtel at Balbec.

And with Proust’s health and anxiety problems, hotels also afforded him an opportunity for rest and recuperate. Biographer Jean-Yves Tadié notes that on July of 1908 Proust left Paris for the Le Grand Hôtel “where he immediately took to bed.”

Proust had stayed at Le Grand Hôtel the previous summer during its grand opening season. Le Figaro lauded it as a “veritable Arabian Nights palace” with modern amenities, including an “American bar.”

Proust, by all accounts, was an exceptional hotel guest. During a seasonal stay at the Hotel Splendide (now gone) in Evian, France, Tadié writes: “Just as Marcel was leaving the hotel, he noted that the receptionist had come to tell him he had ‘never known anyone who was so generous to the staff,’ ‘that all employees were devoted to him’, even though he asked so much of them.’”

Transience and Continuity.

If you are fortunate to stay in a hotel for an extended period of time, you have time to appreciate the choregraphed transience of the whole affair. The guests come and go, like dancers on a stage, excitable and fanciful, yet always carefully directed by the continuity, routine, and repetition of the staff and the institution. The dramatis personae are ever changing, but the ancient Frangipani trees at the Continental Hotel Saigon, for example, remain as always.

Sitting in a lobby with a cocktail and studying the guests is an underappreciated pleasure. You spot a particularly stylish, cosmopolitan couple. Are they from Hong Kong, Vancouver, or maybe Los Angeles? Are they seasoned travelers or is this a singular trip, never to be repeated, due to financial restraints or impending marital troubles? Is the woman’s British-accented, though not-native English, evidence she studied in London, or perhaps she went to an international school in Singapore?

It's all great fun, and when you finish your drink, you return to your immaculately clean room, where the bed sheets have been changed and the towels replenished, and you find it is time for a bit of Johnny Walker Black, or a nap, or better yet, one followed by the other.

The Heart of French Saigon.

If you fall in love with Ho Chi Minh City in Vietnam, there is a fair chance the Hotel Continental Saigon will soon get your attention too, expanding your intimate affair into something much more, a menage a trois, if you will, along the Saigon River.

There is an undeniable symbiosis between the city and the hotel. This is partly due to the Continental’s rank as the city’s oldest, but more broadly, because the colonial architecture of the building—the perfect embodiment of L'indochine Française—has, over time, become a reflection of the city’s charms and complexities: that familiar legacy of beauty, guilt, ambition, shame, and power, so bound up with European colonialism in the tropics.

The late Anthony Bourdain adored the Continental because of its connections with Graham Greene and his famed 1955 novel The Quiet American. Graham lived at the Continental during repeated trips to Vietnam as a foreign correspondent between 1952 and 1955. He wrote part of the novel in room 214, and he often held court at Le Bourgeois Restaurant on the first floor.

Solitude and Freedom.

The dirty secret about writers is that when the work is going well—and the work is rarely going well—we don’t give a damn about ordinary life and relationships. When we suspect, perhaps this one time, we might land the plane, write something great—then all that matters is the yoke and landing strip.

Hotels serve working writers by offering the most precious of commodities: solitude and freedom. There is a maid to clean the room, a staff to make the meals and fix the drinks, and if writer’s block begins to nag at you, you can slip downstairs into the lobby, space out in an armchair, and gradually lull yourself back into the dream.

And when the work is done for the day, and it’s time to call on friends, who doesn’t enjoy a drink at a hotel bar? You take the elevator downstairs, and voila, your workplace is transformed into a watering hole for your friends and peers.

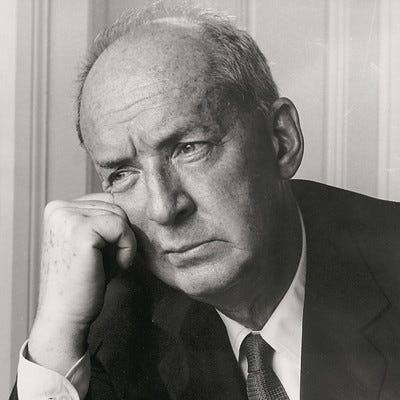

The Master in Montreux.

There are some hotels, such as the Mandarin Oriental, Bangkok, which are known less for an association with one writer, but a full roster of them.

The Oriental’s marketing content boasts of a young Joseph Conrad taking room and board as a merchant marine officer, the Japanese master Yukio Mishima was a guest while researching temple Wat Arun for his novel The Temple of Dawn, and frequent guest Somerset Maugham, who got malaria in Siam, and wrote years later: “I was almost evicted from The Oriental because the manager did not want me to ruin her business by dying in one of her rooms.”

In most cases, these writers stayed for a brief time. Likely longer than our harried, in-and-out travel itineraries today, but still recognizable as vacation-length affairs.

But then there are examples where hotels and writers commit to one another, and in the case of Vladimir Nabokov, the commitment was for life.

Nabokov lived at the Fairmont Le Montreux Palace in Montreux, Switzerland for 16 years, from 1961 until his death in 1977. He was by then, the world-famous writer of Lolita, the Russian aristocratic exile, who’d worked and taught in the United States for years, before moving to Switzerland.

In 1969 Time magazine sent a correspondent to Montreux to interview him. “The hotel is a vast rococo establishment. In the offseason, the staff tends to outnumber the 20-odd guests,” the magazine reported. “Twice a day (the guests) gather in the Winter Dining Room, a smallish chamber in the hotel basement, which, despite lavish importation of daffodils and red tulips, is a frightful miniature of desolation. All guests have their own tables; there is almost no talk. The Nabokovs have a cook and eat here only when they have visitors.”

Two years earlier, The Paris Review also made a trek to the hotel:

“(The Nabokovs) dwell in a connected series of hotel rooms that, like their houses and apartments in the United States, seem impermanent, places of exile. Their rooms include one used for visits by their son Dmitri, and another, the chambre de debarras, where various items are deposited—Turkish and Japanese editions of Lolita, other books, sporting equipment, an American flag.

Nabokov arises early in the morning and works. He does his writing on filing cards, which are gradually copied, expanded, and rearranged until they become his novels. During the warm season in Montreux, he likes to take the sun and swim at a pool in a garden near the hotel.”

Epilogue, or Maybe a Coda.

A good hotel, particularly an old one, manages to do the impossible. It creates an illusion, a fairytale of timelessness. Writers, who are nothing but spinners of fairy tales themselves, naturally fall for such a lovey scheme.

If you’ve been abroad much lately, you know that travel—still intriguing and worthwhile—is also more vulgar than ever. It is mass market experience. Everyone, it seems, has either been to Thailand, Venice, Croatia, etc.—or is planning on going there.

I suspect the grandeur, the beauty—and the almost stupefying impracticality—of a hotel like Fairmont Le Montreux Palace, is how most people now view serious, important, substantive novels like Moby Dick, Gravity’s Rainbow, The Sound and The Fury or The Wings of a Dove.

It doesn’t mean the novel is dead, or that nobody will read anymore. People still attend the opera, after all, or listen to Mozart symphonies. It’s simply an observation that staying at a place like Le Grand Hôtel in Cabourg or reading Swann’s Way are now both ridiculously niche activities, done by a tiny subculture of enthusiasts.

It’s far more likely that somehow in your neighborhood will sky dive, tattoo their face, consume hallucinogenic mushrooms, or steal an automobile before they even consider reading Crime and Punishment—and that’s on the rather tenuous presumption that they’ve even heard of the book.

So, finally, what would an essay on writers and hotels be without an inimitable quote from Oscar Wilde? On this deathbed at L’Hôtel d'Alsace (now L'Hôtel) in Paris, he reportedly quipped: "This wallpaper and I are fighting a duel to the death. One of us has got to go."

###

Robert Fay is an Oregon-based writer who has written for The Atlantic, The Los Angeles Review of Books, First Things, The Chicago Quarterly Review, and others publications.